Scientific American, Volume XLIII., No. 25, December 18, 1880, by Various, is part of the HackerNoon Books Series. You can jump to any chapter in this book here. BUSINESS COLLEGES.

BUSINESS COLLEGES.

PACKARD'S BUSINESS COLLEGE.

There are two very general prejudices against the class of schools known as business colleges. One is that their chief aim—next to lining the pockets of their proprietors—is to turn out candidates for petty clerkships, when the country is already overrun with young men whose main ambition is to stand at a desk and "keep books." The other is that the practical outcome of these institutions is a swarm of conceited flourishers with the pen, who, because they have copied a set or two of model account books and learned to imitate more or less cleverly certain illegibly artistic writing copies, imagine themselves competent for any business post, and worthy of a much higher salary than any merely practical accountant who has never been to a business college or attempted the art of fancy penmanship as exhibited in spread eagles and impossible swans.

As a rule popular prejudices are not wholly unfounded in reason; and we should not feel disposed to make an exception in this case. When the demand arose for a more practical schooling than the old fashioned schools afforded, no end of writing masters, utterly ignorant of actual business life and methods, hastened to set up ill managed writing schools which they dubbed "business colleges," and by dint of advertising succeeded in calling in a multitude of aspirants for clerkships. In view of the speedy discomfiture of the deluded graduates of such schools when brought face to face with actual business affairs, and the disgust of their employers who had engaged them on the strength of their alleged business training, one is not so much surprised that prejudice against business colleges still prevails in many quarters, as that the relatively few genuine institutions should have been able to gain any creditable footing at all.

The single fact that they have overcome the opprobrium cast upon their name by quacks, so far as to maintain themselves in useful prosperity, winning a permanent and honorable place among the progressive educational institutions of the day, is proof enough that they have a mission to fulfill and are fulfilling it. This, however, is not simply, as many suppose, in training young men and young women to be skilled accountants—a calling of no mean scope and importance in itself—but more particularly in furnishing young people, destined for all sorts of callings, with that practical knowledge of business affairs which every man or woman of means has constant need of in every-day life. Thus the true business college performs a twofold function. As a technical school it trains its students for a specific occupation, that of the accountant; at the same time it supplements the education not only of the intending merchant, but equally of the mechanic, the man of leisure, the manufacturer, the farmer, the professional man—in short, of any one who expects to mix with or play any considerable part in the affairs of men. The mechanic who aspires to be the master of a successful shop of his own, or foreman or manager in the factory of another, will have constant need of the business habits and the knowledge of business methods and operations which a properly conducted business school will give him. The same is true of the manufacturer, whose complicated, and it may be extensive, business relations with the producers and dealers who supply him with raw material, with the workmen who convert such material into finished wares, with the merchants or agents who market the products of his factory, all require his oversight and direction. Indeed, whoever aspires to something better than a hand-to-mouth struggle with poverty, whether as mechanic, farmer, professional man, or what not, must of necessity be to some degree a business man; and in every position in life business training and a practical knowledge of financial affairs are potent factors in securing success.

How different, for example, would have been the history of our great inventors had they all possessed that knowledge of business affairs which would have enabled them to put their inventions in a business like way before the world, or before the capitalists whose assistance they wished to invoke. The history of invention is full of illustrations of men who have starved with valuable patents standing in their names—patents which have proved the basis of large fortunes to those who were competent to develop the wealth that was in them. How often, too, do we see capable and ingenious and skillful mechanics confined through life to a small shop, or to a subordinate position in a large shop, solely through their inability to manage the affairs of a larger business. On the other hand, it is no uncommon thing to see what might be a profitable business—which has been fairly thrust upon a lucky inventor or manufacturer by the urgency of popular needs—fail disastrously through ignorance of business methods and inability to conduct properly the larger affairs which fell to the owner's hand.

Of course a business training is not the only condition of success in life. Many have it and fail; others begin without it and succeed, gaining a working knowledge of business affairs through the exigencies of their own increasing business needs. Nevertheless, in whatever line in life a man's course may fall, a practical business training will be no hinderance to him, while the lack of it may be a serious hinderance. The school of experience is by no means to be despised. To many it is the only school available. But unhappily its teachings are apt to come too late, and often they are fatally expensive. Whoever can attain the needed knowledge in a quicker and cheaper way will obviously do well so to obtain it; and the supplying of such practical knowledge, and the training which may largely take the place of experience in actual business, is the proper function of the true business college.

Our purpose in this writing, however, was not so much to enlarge upon the utility of business colleges, properly so called, as to describe the practical working of a representative institution, choosing for the purpose Packard's Business College in this city.

This school was established in 1858, under the name of Bryant, Stratton & Packard's Mercantile College, by Mr. S. S. Packard, the present proprietor. It formed the New York link in the chain of institutions known as the Bryant & Stratton chain of business colleges, which ultimately embraced fifty co working schools in the principal cities of the United States and Canada. In 1867 Mr. Packard purchased the Bryant & Stratton interest in the New York College, and changed its name to Packard's Business College, retaining the good will and all the co operative advantages of the Bryant & Stratton association. The original purpose of the college, as its name implies, was the education of young men for business pursuits. The experience of over twenty years has led to many improvements in the working of the school, and to a considerable enlargement of its scope and constituency, which now includes adults as well as boys, especial opportunities being offered to mature men who want particular instruction in arithmetic, bookkeeping, penmanship, correspondence, and the like.

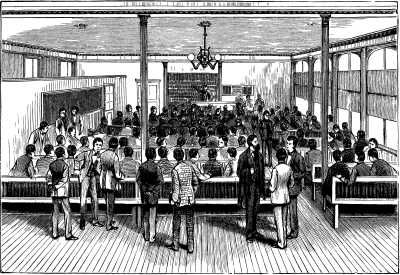

The teachers employed in the college are chosen for their practical as well as their theoretical knowledge of business affairs, and every effort is made to secure timeliness and accuracy in their teachings. Constant intercourse is kept up with the departments at Washington as to facts and changes in financial matters, and also with prominent business houses in this and other cities. Among the recent letters received in correspondence of this sort are letters from the Secretary of State of every State in the Union with regard to rates of interest and usury laws, and letters from each of our city banks as to methods of reckoning time on paper, the basis of interest calculations, the practices concerning deposit balances, and other business matters subject to change. The aim of the proprietor is to keep the school abreast of the demands of the business world, and to omit nothing, either in his methods or their enforcement, necessary to carry out his purpose honestly and completely. An idea of the superior housing of the college will be obtained from the views of half a dozen of the rooms at No 805 Broadway, as shown in this issue of the Scientific American—the finest, largest, most compact, and convenient suite of rooms anywhere used for this purpose.

The college is open for students ten months of the year, five days each week, from half past nine in the morning until half past two in the afternoon. Students can enter at any time with equal advantage, the instruction being for the most part individual. The course of study can be completed in about a year. The proprietor holds that with this amount of study a boy of seventeen should be able—

1. To take a position as assistant bookkeeper in almost any kind of business; 2. To do the ordinary correspondence of a business house, so far as good writing, correct spelling, grammatical construction, and mechanical requisites are concerned; 3. To do the work of an entry clerk or cashier; 4. To place himself in the direct line of promotion to any desirable place in business or life, with the certainty of holding his own at every step.

In this the student will have the advantage over the uneducated clerk of the same age and equal worth and capacity, in that he will understand more or less practically as well as theoretically the duties of those above him, and will thus be able to advance to more responsible positions as rapidly as his years and maturity may justify. It is obvious that the knowledge which makes an expert accountant will in all probability suffice for the general business requirements of professional men, the inheritors of property and business, manufacturers, mechanics, and others to whom bookkeeping and other business arts are useful aids, but not the basis of a trade. For the last-named classes, and for women, shorter periods of study are provided, and may be made productive of good results.

A sufficient idea of the general working of the college may be obtained by following a student through the several departments. After the preliminary examination a student who is to take the regular course of study enters the initiatory room. Here he begins with the rudiments of bookkeeping, the study which marks his gradation. The time not given to the practice of writing, and to recitations in other subjects, is devoted to the study of accounts. He is required, first, to write up in "skeleton" form—that is, to place the dates and amounts of the several transactions under the proper ledger titles—six separate sets of books, or the record of six different business ventures, wherein are exhibited as great a variety of operations as possible, with varying results of gains and losses, and the adjustment thereof in the partners' accounts, or in the account of the sole proprietor. After getting the results in this informal way—which is done in order as quickly as possible to get the theory of bookkeeping impressed upon his mind—he is required to go over the work again carefully, writing up with neatness and precision all the principal and auxiliary books, with the documents which should accompany the transactions, such as notes, drafts, checks, receipts, invoices, letters, etc. The work in this department will occupy an industrious and intelligent student from four to six weeks, depending upon his quickness of perception and his working qualities. While progressing in his bookkeeping, he is pursuing the collateral studies, a certain attainment in which is essential to promotion, especially correcting any marked deficiency in spelling, arithmetic, and the use of language.

Upon a satisfactory examination the student now passes to the second department, where a wider scope of knowledge in accounts is opened to him, with a large amount of practical detail familiarizing him with the actual operations of business. The greatest care is taken to prevent mere copying and to throw the student upon his own resources, by obliging him to correct his own blunders, and to work out his own results; accepting nothing as final that has not the characteristics of real business. Much care is bestowed in this department upon the form and essential matter of business paper, and especially of correspondence. A great variety of letters is required to be written on assigned topics and in connection with the business which is recorded, and thorough instruction is given in the law of negotiable paper, contracts, etc. During all this time the student devotes from half an hour to an hour daily to penmanship, a plain, practical, legible hand being aimed at, to the exclusion of superfluous lines and flourishes. It is expected that the work in the first and second departments will establish the student in the main principles of bookkeeping, in its general theories, and their application to ordinary transactions.

In the third department the student takes an advanced position, and is expected, during the two or three months he will remain in this department, to perfect himself in the more subtle questions involved in accounts, as well as to shake off the crude belongings of schoolboy work. He will be required to use his mind in everything he does—to depend as much as possible upon himself. The work which he presents for approval here must have the characteristics of business. His letters, statements, and papers of all kinds are critically examined, and approved only when giving evidence of conscientious work, as well as coming up to strict business requirements. Before he leaves this department he should be versed in all the theories of accounts, should write an acceptable business hand; should be able to execute a faultless letter so far as relates to form, spelling, and grammatical construction, should have a fair knowledge of commercial law, and have completed his arithmetical course.

The next step is to reduce the student's theoretical knowledge to practice, in a department devoted to actual business operations. This business or finishing department is shown at the upper left corner of our front page illustration. The work in this department is as exacting and as real as the work in the best business houses and banks. At the extreme end of the room is a bank in complete operation, as perfect in its functions as any bank in this city or elsewhere. The records made in its books come from the real transactions of dealers who are engaged in different lines of business at their desks and in the offices. The small office adjoining the bank, on the right, is a post office, the only one in the country, perhaps, where true civil service rules are strictly observed. In connection with it is a transportation office. From fifty to a hundred letters daily are received and delivered by the post office, written by or to the students of this department.

The correspondence thus indicated goes on not only between the students of this college, but between members of this and other similar institutions in different parts of the country. A perfected system of intercommunication has for years been in practice between co-ordinate schools in New York, Boston, Brooklyn, Philadelphia, Chicago, Baltimore, and other cities, by which is carried on an elaborate scheme of interchangeable business, little less real in its operations and results than the more tangible and obtrusive activity which the world recognizes as business.

The work of the transportation office corresponds with that of the post office in its simulation of reality. The alleged articles handled are represented by packages bearing all the characteristic marks of freight and express packages. They are sent by mail to the transportation company, and by this agency delivered to the proper parties, from whom the charges are collected in due form, and the requisite vouchers passed. Whatever is necessary in the way of manipulation to secure the record on either hand is done, and, so far as the clerical duties are concerned, there is no difference between handling pieces of paper which represent merchandise and handling the real article.

In the bank is employed a regular working force, such as may be found in any bank, consisting of a collector or runner, a discount clerk, a deposit bookkeeper, a general bookkeeper, and a cashier. The books are of the regular form, and the work is divided as in most banks of medium size, and the business that is presented differs in no important particular from that which comes to ordinary banks. After getting a fair knowledge of theory, the student is placed in this bank. He begins in the lowest place, and works up gradually to the highest, remaining long enough in each position to acquaint himself with its duties. He is made familiar with the form and purpose of all kinds of business paper, and the rules which govern a bank's dealings with its customers. He gets a practical knowledge of the law of indorsement and of negotiability generally, and is called upon to decide important questions which arise between the bank and its dealers. Wherever he finds himself at fault he has access to a teacher whose duty it is to give the information for which he asks, and who is competent to do it.

Throughout the whole of this course of study and practice the students are treated like men and are expected to behave like men.

The college thus becomes a self-regulating community, in which the students learn not only to govern themselves, but to direct and control others. As one is advanced in position his responsibilities are increased. He is first a merchant or agent, directing his own work; next, a sub-manager, and finally manager in a general office or the bank, with clerks subject to his direction and criticism, until he arrives at the exalted position of "superintendent of offices," which gives him virtual control of the department. This is, in fact, an important part of his training, and the reasonable effect of the system is that the student, being subject to orders from those above him, and remembering that he will shortly require a like consideration from those below him, concludes that he cannot do a better thing for his own future comfort than to set a wholesome example of subordination.

This, however, is not the only element of personal discipline that the college affords. At every step the student's conduct, character, and progress are noted, recorded, and securely kept for the teacher's inspection, as well as that of his parents and himself. Such records are kept in the budget room, shown in the lower left corner of the front page.

This budget system was suggested by the difficulties encountered in explaining to parents the progress and standing of their sons. The inconvenience of summoning teachers, and of taking students from their work, made necessary some simpler and more effective plan. The first thing required of a new student is that he should give some account of himself, and to submit to such examinations and tests as will acquaint his teachers with his status. This account and these tests constitute the subject-matter of his first budget, which is placed at the bottom of his box, and every four weeks thereafter, while he remains in the school, he is required to present the results of his work, such as his written examinations in the various studies, his test examples in arithmetic, his French, German, and Spanish translations and exercises, various letters and forms, with four weekly specimens of improvement in writing, the whole to be formally submitted to the principal in an accompanying letter; the letter itself to exhibit what can be thus shown of improvement in writing, expression, and general knowledge. These budgets, accumulating month by month, are made to cover as much as possible of the student's school work, and to constitute the visible steps of his progress.

Besides this is a character record, kept in a small book assigned to each student, every student having free access to his own record, but not to that of any fellow student. Each book contains the record of a student's deportment from the first to the last day of his attendance, with such comments and recommendations as his several teachers may think likely to be of encouragement or caution to him.

In addition to the strictly technical training furnished by the college, there is given also not a little collateral instruction calculated to be of practical use to business men. For example, after roll call every morning some little time is spent in exercises designed to cultivate the art of intelligent expression of ideas. Each day a number of students are appointed to report orally, in the assembly room, upon such matters or events mentioned in the previous day's newspapers as may strike the speaker as interesting or important. Or the student may describe his personal observation of any event, invention, manufacture, or what not; or report upon the condition, history, or prospects of any art, trade, or business undertaking. This not to teach elocution, but to train the student to think while standing, and to express himself in a straightforward, manly way.

Instruction is also given in the languages likely to be required in business intercourse or correspondence; in phonography, so far as it may be required for business purposes; commercial law relative to contracts, negotiable paper, agencies, partnerships, insurance, and other business proceedings and relations; political economy, and incidentally any and every topic a knowledge of which may be of practical use to business men.

In all this the ultimate end and aim of the instruction offered are practical workable results. Mr. Packard regards education as a tool. If the tool has no edge, is not adapted to its purpose, is not practically usable, it is worthless as a tool. This idea is kept prominent in all the work of the college, and its general results justify the position thus taken. The graduates are not turned out as finished business men, but as young men well started on the road toward that end. As Mr. Packard puts it: "Their diplomas do not recommend them as bank cashiers or presidents, or as managers of large or small enterprises, but simply as having a knowledge of the duties of accountantship. They rarely fail to fulfill reasonable expectations; and they are not responsible for unreasonable ones."

About HackerNoon Book Series: We bring you the most important technical, scientific, and insightful public domain books.

This book is part of the public domain. Various (2007). Scientific American, Volume XLIII., No. 25, December 18, 1880. Urbana, Illinois: Project Gutenberg. Retrieved https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/21081/pg21081-images.html

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org, located at https://www.gutenberg.org/policy/license.html.