Authors:

(1) PIOTR MIROWSKI and KORY W. MATHEWSON, DeepMind, United Kingdom and Both authors contributed equally to this research;

(2) JAYLEN PITTMAN, Stanford University, USA and Work done while at DeepMind;

(3) RICHARD EVANS, DeepMind, United Kingdom.

Table of Links

Storytelling, The Shape of Stories, and Log Lines

The Use of Large Language Models for Creative Text Generation

Evaluating Text Generated by Large Language Models

Conclusions, Acknowledgements, and References

A. RELATED WORK ON AUTOMATED STORY GENERATION AND CONTROLLABLE STORY GENERATION

B. ADDITIONAL DISCUSSION FROM PLAYS BY BOTS CREATIVE TEAM

C. DETAILS OF QUANTITATIVE OBSERVATIONS

E. FULL PROMPT PREFIXES FOR DRAMATRON

F. RAW OUTPUT GENERATED BY DRAMATRON

2 STORYTELLING, THE SHAPE OF STORIES, AND LOG LINES

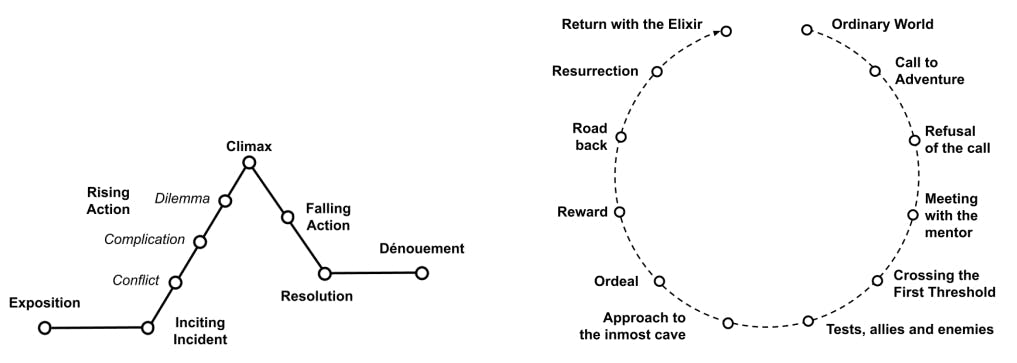

Archaeological evidence including artists’ depictions of narratives on jars from as far back as 2400 BCE, show how ancient societies used the technologies of their time to help tell their stories [43]. In Poetics [5], Aristotle identified plot (or mythos) as the most important part of a tragic story—the other elements being characters, their thoughts, language, melody and spectacle. The plot is the sequence of actions that shape the story. Each plot point is coherent with, and a consequence of, the previous point(s). Aristotle introduced the well-known simple 3-point plot: beginning, middle, and end. There are many dramatic structures extending the work of Aristotle [82]. For example, one of the many adaptations of Freytag’s pyramid [40], popular in Western storytelling is illustrated in Fig. 2. It includes this sequence of plot points: Exposition, Inciting Incident, a Rising Action composed of a series of Conflicts, Complications, and Dilemmas, Climax, Falling Action, Resolution, and Dénouement. Seminal work in narrative analysis [58, 83, 93] suggests general but mutable structures present in storytelling processes across many linguistic and cultural traditions (e.g. abstract, orientation, complicating action, and coda narrative clauses). The finding that narratives in many societies and in various languages make use of large, modular elements has inspired the use of models of narrative in automated storytelling, as can be seen in fields such as computational narratology [53, 63]. The general structures found in the Structuralist narratology of Propp [83] and the Personal Experience Narratives of Labov and Waletzky [58] are aligned with Freytag’s pyramid, which we choose because it is more in line with the specific discourse genre of dramatic scripts, and arguably more familiar to the playwrights we engaged with over the course of our study. However, we note that our choice of narrative structure is not universal in scope, and is, in fact, "characteristically Western" [26, 53]. Alternative story shapes, or "story grammars" [94] are possible [6, 17]. Fig. 2 also shows an alternative story structure: the Hero’s Journey or Monomyth [15, 110]. For narrative coherence, we leverage plot beats in our hierarchical generation.

Oftentimes the seed of narrative inspiration for a screenplay or theatre script is a log line [98]. The log line summarizes the story in a few sentences and is often adapted over the course of production due to creative team preferences and cultural references. Log lines typically contain the setting, protagonist, antagonist, a conflict or goal, and sometimes the inciting incident [8]. In this work, we use log lines to start the hierarchical story generation process because it contains plot elements in the answers to questions: Who? What? When and Where? How? Why? [101]

This paper is available on arxiv under CC 4.0 license.