Scientific American Supplement, No. 717, September 28, 1889, by Various, is part of the HackerNoon Books Series. You can jump to any chapter in this book here. THE SHIP IN THE NEW FRENCH BALLET OF THE "TEMPEST."

THE SHIP IN THE NEW FRENCH BALLET OF THE "TEMPEST."

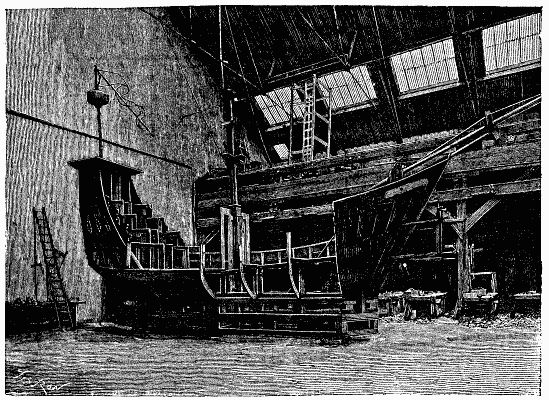

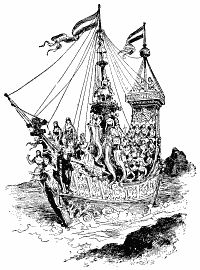

A new ballet, entitled the "Tempest," by Messrs. Barbier and Thomas, has recently been put upon the stage of the Opera at Paris with superb settings. One of the most important of the several tableaux exhibited is the last one of the third act, in which appears a vessel of unusual dimensions for the stage, and which leaves far behind it the celebrated ships of the "Corsaire" and "L'Africaine." This vessel, starting from the back of the stage, advances majestically, describes a wide circle, and stops in front of the prompter's box.

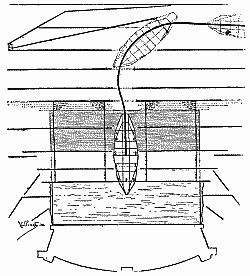

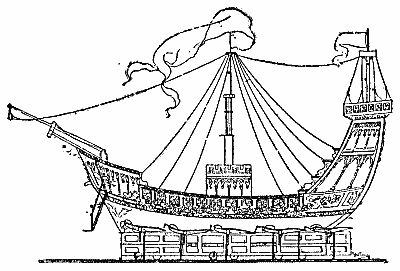

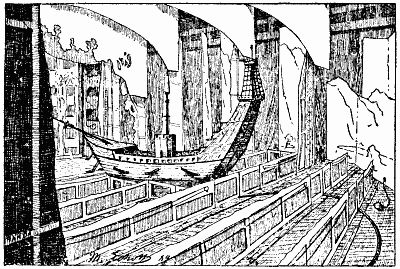

As the structure of this vessel and the mechanism by which it is moved are a little out of the ordinary, we shall give some details in regard to them. First, the sea is represented by four parallel strips of water, each formed of a vertical wooden frame entirely free in its movements (Fig. 2). The ship (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5) is carried by wheels that roll over the floor of the stage. It is guided in its motion by two grooved bronze wheels and by a rail formed of a simple reversed T-iron which is fixed to the floor by bolts. In measure as it advances, the strips of water open in the center to allow it to pass, and, as the vessel itself is covered up to the water line with painted canvas imitating the sea, it has the appearance of cleaving the waves. As soon as it has passed, the three strips of water in the rear rise slightly. When the vessel reaches the first of the strips, the three other strips, at first juxtaposed against the preceding, spread out and thus increase the extent of the sea, while the inclined plane of the preceding tableau advances in order to make place for the vessel. The shifting of this inclined place is effected by simply pulling upon the carpet that covers it, and which enters a groove in the floor in front of the prompter's box. At this moment, the entire stage seems to be in motion, and the effect is very striking.

We come now to the details of construction of the vessel. It is not here a question of a ship represented simply by means of frames and accessories, but of a true ship in its entirety, performing its evolutions over the whole stage. Now, a ship is not constructed at a theater as in reality. It does not suffice to have it all entire upon the stage, but it is necessary also to be able to dismount it after every representation, and that, too, in a large number of pieces that can be easily stored away. Thus, the vessel of the Tempest, which measures a dozen yards from stem to stern, and is capable of carrying fifty persons, comes apart in about 250 pieces of wood, without counting all the iron work, bolts, etc. Nevertheless, it can be mounted in less than two hours by ten skilled men.

The visible hull of the ship is placed upon a large and very strong wooden framework, formed of twenty-six trusses. In the center, there are two longitudinal trusses about three feet in height by twenty-five in length, upon which are assembled, perpendicularly, seven other trusses. In the interior there are six transverse pieces held by stirrup bolts, and at the extremity of each of these is fixed a thirteen-inch iron wheel. It is upon these twelve wheels that the entire structure rolls.

There are in addition the two bronze guide wheels that we have already spoken of. In the rear there are two large vertical trusses sixteen feet in height, which are joined by ties and descend to the bottom of the frame, to which they are bolted. These are worked out into steps and constitute the skeleton of the immense stern of the vessel. The skeleton of the prow is formed of a large vertical truss which is bolted to the front of the frame and is held within by a tie bar. On each side of this truss are placed the parallels (Figs. 1 and 3), which are formed of pieces of wood that are set into the frame below and are provided above with grooves for the passage of iron rods that support the foot rests by means of which the supernumeraries are lifted. As a whole, those rods constitute a jointed parallelogram, so that the foot rest always remains horizontal while describing a curve of five feet radius from the top of the frame to the deck of the vessel. They are actuated by a cable which winds around a small windlass fixed in the interior of the frame.

The large mast consists of a vertical sheath 10 ft. high, which is set into the center of the frame, and in the interior of which slides a wooden spar that exceeds it by 5 ft. at first, and is capable of being drawn out as many more feet for the final apotheosis. This part of the mast carries three footboards and a platform for the reception of "supers." It is actuated by a windlass placed upon the frame.

To form the skeleton of the vessel there are mounted upon the frame a series of eight large vertical trusses parallel with each other and cross-braced by small trusses. The upper part of these supports the flooring of the deck, and their exterior portion affects the curve of a ship's sides. It is to these trusses that are attached the panels covered with painted canvas that represent the hull. These panels are nine in number on each side. Above are placed those that simulate the nettings and those that cover the prow or form its crest.

The turret that surrounds the large mast is formed of vertical trusses provided with panels of painted canvas and carrying a floor for the figurants to stand upon.

The bowsprit is in two parts, one sliding in the other. The front portion is at first pulled back, in order to hide the vessel entirely in the side scenes. It begins to make its appearance before the vessel itself gets under way. Light silken cordages connect the mast, the bowsprit, and the small mast at the stern.

On each side of the vessel, there are bolted to the frame that supports it five iron frames covered with canvas (Fig. 3), which reach the level of the water line, and upon which stand the "supers" representing the naiads that are supposed to draw the ship upon the beach. Finally at the bow there is fixed a frame which supports a danseuse representing the living prow of the vessel.

The vessel is drawn to the middle of the stage by a cable attached to its right side and passing around a windlass placed in the side scenes to the left (Fig. 2). It is at the same time pushed by machinists placed in the interior of the framework. The latter, as above stated, is entirely covered with painted canvas resembling water.

As the vessel, freighted with harmoniously grouped spirits, and with naiads, sea fairies, and graceful genii seeming to swim around it, sails in upon the stage, puts about, and advances as if carried along by the waves to the front of the stage, the effect is really beautiful, and does great credit to the machinists of the Opera.

We are indebted to Le Genie Civil and Le Monde Illustré for the description and engravings.

About HackerNoon Book Series: We bring you the most important technical, scientific, and insightful public domain books.

This book is part of the public domain. Various (2006). Scientific American Supplement, No. 717, September 28, 1889. Urbana, Illinois: Project Gutenberg. Retrieved https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/17755/pg17755-images.html

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org, located at https://www.gutenberg.org/policy/license.html.